News - The new book about Artsakh's museums — a call to safeguard Armenian heritage.

Business Strategy

The new book about Artsakh's museums — a call to safeguard Armenian heritage.

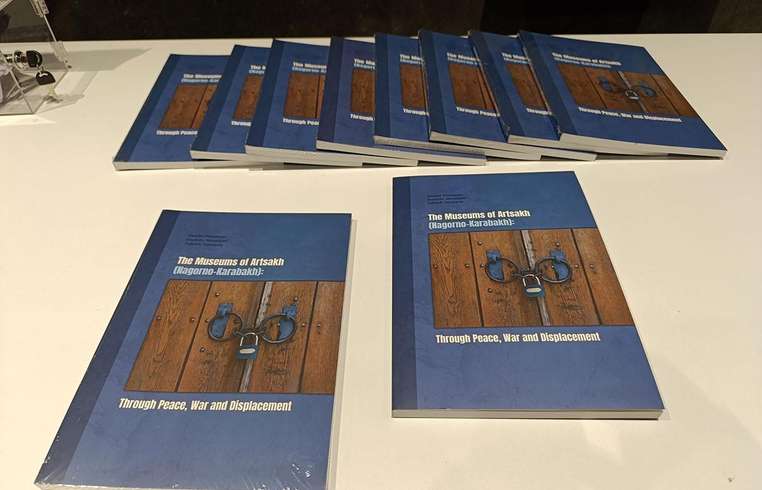

On the blue-bound book cover there is a locked wooden door. It carries us to Artsakh, tracing the paths of cultural heritage. The lock also serves as a warning bell to remind us to continue unfinished tasks and to act quickly. With financial support from the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), the book Artsakh's Museums under Conditions of Peace, War, and Forced Displacement has been published. It is a documentary account of Artsakh's museum life, from the formation and development of museums to the days of the forcibly displaced Artsakh Armenians. This is a scientifically valuable study based on on-site research and documentary material. In the book memory flows like a relay and reaches our days: what cultural heritage we left in Artsakh, how cultural life developed there, how the museums became a vital space for people, what legal instruments are needed to protect and restore the cultural heritage that remains in Artsakh, and so on. The book consists of three parts. The first part traces the historical path of the formation and operation of museums—from the Soviet era to Artsakh's liberation movement, then the period of Artsakh's independence, from independence to the 2020 44-day war, when under independence new museums and collections were created, funds and displays were augmented and expanded, contributing to the activation of Artsakh's cultural life. The second part presents the history of state and private museums, the formation of collections, their significance and their role in shaping communal memory. Here, Artsakh's museums are individually presented—from their founding to forced displacement, then the subsequent preservation of cultural heritage. The last chapter discusses issues related to international legal regulation concerning the protection of missing and displaced museums and collections. It analyzes in detail to what extent international mechanisms have been applicable in the context of the 44-day war and the 2023 forced displacement. The authors of the book are Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Hamlet Petrosyan, head of the Artsakh historical-cultural heritage studies group at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the NAS of Armenia, and candidates of Historical Sciences Haykuhi Muradyan and Nzhdeh Yeranyan, researchers in the same Artsakh heritage studies group. “This book's launch is by no means a cause for joy for me. The launch is meant to make us a little more cautious, that people who know something about culture show a somewhat different attitude; otherwise, what is the force of culture and its role in creation? With this aim we created the book,” Petrosyan said at the launch. “Cultural heritage has long been the flag that leads the Armenian people; our textbooks and scholarly books are full of it, because this culture is a bright thing that leads us to a bright place. Yet today we are in a situation where we feel how that culture is subjected to losses.” Dr. Petrosyan expressed gratitude to his colleagues who helped carry out this work, noting that the team comprised 15–16 people, and added that he hopes to continue the effort since the work cannot be reconciled with political conjuncture. “We have lost heritage,” the scientist stated. Co-author Nzhdeh Yeranyan added that, by being in Artsakh through various research programs, he has seen how much work has been done there with small efforts, and that this book is primarily a tribute to all Artsakh's museums and to all those at the roots of shaping cultural life—from fund custodians and guards to ministers. “I kept thinking of my colleague Marat, who had a great devotion and contribution to Artsakh's museum and monument sector, but who sadly died in a gas-station explosion,” Yeranyan said. According to the speaker, museums, as places for preserving cultural values, existed in Artsakh since the Middle Ages, as evidenced by written records and documents describing how museums formed around various monasteries from the 12th–13th centuries onward. Monuments and gravestones were routinely gathered; perhaps in the classical sense the museums formed later, but it is clear that particular importance was given to these cultural objects— including manuscripts we have information about, the Artsakh cultural heritage researcher notes. Nevertheless, the first classic museum institutions in Artsakh formed during the Soviet years. The first was the Stepanakert State Museum of History and Local Lore, founded in 1937. This was sparked by the discovery of an accidental burial near Stepanakert, in the Krzhani area. “This was something else: although it followed the Soviet museum concept and was designed to present not only local history but also to overcome illiteracy and to present party propaganda, it helped ensure that many artefacts found in Artsakh over the following years remained in Artsakh. Looking at the Azokh (Azykh) cave excavations, we see that the best examples were mainly transported to Baku, but at least the core artefacts stayed in Stepanakert,” Yeranyan explains. In the 1960s–1970s, museum branches were opened in Hadrut (later renamed after Atrúr Mkrtchyan), Martakert and Martuni. This was an important foundation for keeping Artsakh's cultural heritage locally. But achieving this was not easy given the ideology pursued by the Azerbaijani party leadership. After Artsakh's independence, museum life also intensified. In the 2000s new museums were created. Holidays were marked in museums, which became tourist sites, thus living institutions. However, this lively museum life did not last long and ended with the 2020 war and the 2023 displacement of Artsakh’s Armenian population. Museums bearing the burden “The Armenians have long had to carry culture on their shoulders. We went to Artsakh and tried to expand our heritage's reach, meaning, and depth, but in the end we had to bring something on our shoulders and today we do not know how what we brought will be perceived or what will become of it,” Petrosyan says. In 2016, during the four-day war, Petrosyan was in Paris. There he was presenting the results of the Tigranakert excavations, when Sergei Shahverdyan, the Artsakh government’s tourism department head, called to ask him to urgently send the list of Tigranakert Museum exhibits so they could evacuate at least some items. No one then knew how many days the war would last. “At that time I realized with horror that Artsakh's museums did not have an evacuation plan, proper documentation in the face of any serious danger, and that this should have been a lesson. The 44-day war, forgive me, but was also a war of cultural losses,” the scholar notes. During the days of the 2020 war, Petrosyan’s first concern was the Tigranakert Museum, which was very close to the front line. After two weeks of staying home during the pandemic, he contacted the Artsakh Ministry of Culture, and, with two colleagues, traveled to Stepanakert to meet the minister and discuss evacuating the museum exhibits. He proposed starting with the Stepanakert History and Archaeology Museum. “People asked, where are you taking it? This is needed. I said we aren’t taking it anywhere else; we’ll take it and then bring it back with a drum and horn,” he recalls. Azerbaijan regards Artsakh's displaced cultural heritage as its own property. According to Hamlet Petrosyan, Armenia’s task now is to defend and to form legal mechanisms for both moved and Artsakh-based heritage. “The heritage books about Artsakh were optimistic. When, for example, a book about Tigranakert came out, I felt happy, but this book is a warning that we have not achieved anything, that we are on a dangerous stretch of a dangerous road, and this book is aimed at what we must do next,” the speaker says. Asked how Azerbaijan handles Artsakh’s Armenian cultural heritage, the scholar notes that the book presents several facts, and adds that Azerbaijan—unlike Armenia—pursues a very thoughtful, meticulously crafted policy. After the war there were some reports about Azerbaijani soldiers entering Stepanakert's History and Archaeology Museum and causing disorder, but since then there are no clear data. “Today Azerbaijan does not allow anyone to enter Artsakh without permission,” Petrosyan says. Efforts to discuss cultural heritage with Azerbaijan via Russia were attempted but yielded no results: “I participated twice, but whenever the discussion reached Artsakh, six to seven people would come in, sit down and say, you are thieves, you must be hanged, you have taken our country’s property. It is an untenable situation,” the professor notes. International law should not be the sole framework The book Artsakh's Museums under Conditions of Peace, War and Forced Displacement documents not only Artsakh's museums but also the issues of private collections and touches on Artsakh’s contemporary artists. Haykuhi Muradyan, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, says it was important to discuss the private collections afterward, to understand what happened to their holdings, what cultural environments they created in Artsakh, how they functioned during the war and after, how they evacuated their works, and the challenges they currently face, with which cultural centers they collaborate, and what environment they are creating now. “The most interesting part was how artists moved during forced displacement, choosing which works to move. It was not a matter of valuation, but which pieces are suitable to transport and how many works they could move,” Muradyan notes. In her view, after the 2023 displacement some Artsakh artists stated they tried to paint from memory the same canvases they left in Artsakh, but it did not turn out the same. Muradyan also addresses the book’s closing: they tried to analyze how international law could become a tool for protecting Artsakh’s cultural heritage. In this regard, international law largely formed after World War II and aimed to end looting between states during war. The toolkit is codified in UNESCO instruments, the Hague Convention, the Rome Statute, and so on. However, the author argues that these rules seem not to apply to unrecognized states like Artsakh. “Here we have tried to show that while international law seeks to defend the rights of recognized states to their own heritage, it neglects the role of communities’ cultural heritage. Of course there are several conventions, but they do not carry the legal weight of the Hague Convention,” Muradyan says. “Azerbaijan has petitioned UNESCO to return heritage taken out of its state. In that case the owner is territorial, not communal. Yet we stress that if the people who own that heritage are not there, to whom should that heritage belong?” the co-author asks, adding, “Our task is to connect the demand for the return of cultural heritage with the return of Artsakh’s Armenian people—the heritage is created by people.” Since the 2020 war and the 2023 displacement, UNESCO has twice tried to dispatch a delegation to Azerbaijan, but Azerbaijan has refused, saying it can monitor itself. On the other hand, the issue of establishing the status of evacuated heritage remains. Muradyan notes: “Shouldn’t the heritage stored in those boxes belong to the community?” “Our task is to formulate a united position, to show international law its vulnerable points where it does not always apply, and to propose what we can. At least, a scholarly discourse must be developed on these issues,” Muradyan says. Today Armenian scholars are working with the term refugee heritage to demonstrate the problem, engage in scholarly dialogue, and not be constrained by international law.